I was listening to a podcast today(actually a podcast introducing another podcast) and the narrator (who I adore, but who, much to my disappointment, my friends don’t like as well*) describes how he can take failure better than other people because he just always just adds them to his big ball of failure—that they all end up being a story to him. When something bad happens, he immediately thinks of how that is going to turn into story.

Do…do other people not do this?

I always think about my life as if I were a narrator. After something happens, I, too, think about how I would describe it. I usually think about how some bad event was humorous if you described it this way. In this way, generally find my life funny in a bumbling-along way.

This is a precursor to say: I think about all the things I want to write about all the time and I know it would bring me enjoyment to share things with you, but there’s this other side of me that doesn’t actually want people to read it. I’m kind of afraid that something will happen and I’ll just end up being arbitrarily cyberbullied and is posting random content really worth that?

It’s not. But, dear reader, here we are.

So what’s been on my mind for the last couple of weeks was me trying to connect all the different things I’ve learned. I see connections all the time and they make me excited (thanks, humanities education!). When you see everything as connected then you end up feeling like everything is relevant. So I’m just going to try writing out all the things.

¯\_(?)_/¯

Before starting me new job, I just poured over professional development books and I’m still reading them and articles because now I just feel like I’m on a roll. Topics include but are not limited to: design, strategy, facilitating conversations, leading innovative working sessions, how to collaborate, how to give feedback, what leadership means, how to be a ‘quiet’ leader, what service design means, how to create better experiences for people, civic technology, and case studies of how industries have failed.

Recently, I’ve been stuck on how to give good feedback (reading). The need for it, the value of it, the resistance to it. Critique, or feedback sessions, might be more verbalized as a designer because there are professional rituals around evaluating work, but that doesn’t mean that feedback is any better than another profession. And besides that, in any job feedback is useful. And as an individual, I crave feedback in order to get better. Some of this is not great (read: a grades-driven student still wanting affirmation), but some of this is just that I’m used to a level of honesty I don’t feel like I’ve gotten professionally. My parents (all my family) are forthcoming with brutally honest critiques of me and have exercised a life time of restraint on praise. In school, there was a regular mechanism for critical feedback around development goals. Teachers and the group members you worked with. When I was a freelancer, feedback arose naturally as a part of working with clients to deliver a product. But recently as a full-time employee, my reviews were mostly tied to annual reviews where, even if I solicited honest feedback I only got positive comments or nothing (if requested outside of performance review time). I’m not innocent of the “Looks great!!!!!!! :DDDD” feedback. It’s hard to take time to give helpful feedback and sometimes I’m simply not brave enough to give someone negative feedback (though I try!). My coworker recently shared this Harvard Business Review Article: “Research: Vague Feedback Is Holding Women Back” and I wondered how or if I was affected. It’s hard to know without an alternative universe where I’m a dude, but I had already felt the lack of critical feedback and I know I’m far from perfect.

I liked in this book that it talked about the common pitfalls…

- Overcoming the fear. Some people have had really bad experiences and avoid feedback. Some people don’t want to hurt people’s emotions

- Asking for feedback and not listening. I definitely had a classmate from grad school in mind when I read this. He was actually just looking for confirmation and praise on his work.

- Not offering feedback on the right problem. You might offer a solution without understanding the problem. But also, a good teacher might tell you that offering a solution won’t help the person grow their own problem solving abilities 😉

- Giving feedback at the appropriate time. People are not always ready to receive feedback, so don’t feel like you’re always being helpful as the unsolicited-advice fairy.

You can make sure your feedback is valuable by taking time to understand the problem. Ask questions to understand what they’re trying to do and how what you’re seeing accomplishes that. Frame your feedback around that goal.

“If you’re trying to get people to understand the importance of your program, the negative wording here might weaken that message”

“If your’e targeting new users, they might get confused on where to go next with all these options on this page”

I’m excited to practice this the next time I give feedback now!

I also really was fascinated by this article on Why do remote meetings suck so much? because of how the author describes remote meetings (video conferences) only being a stress case for why all meeting dynamics suck so much. If you’re hoping it’s just going to be a bashing of remote meetings, sorry. It’s about the real problems behind why most meetings don’t work and we just learn to unhappily deal with it.

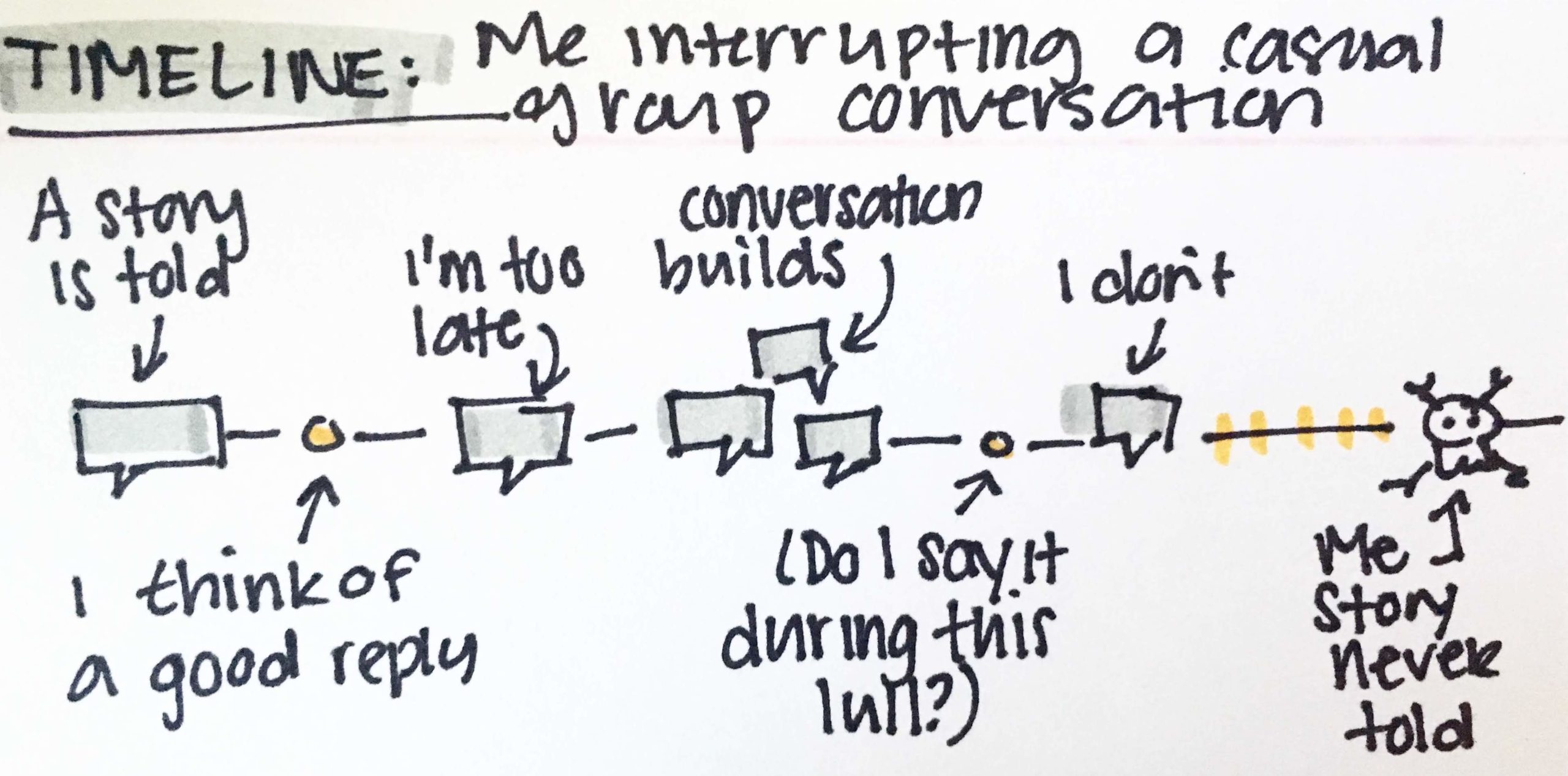

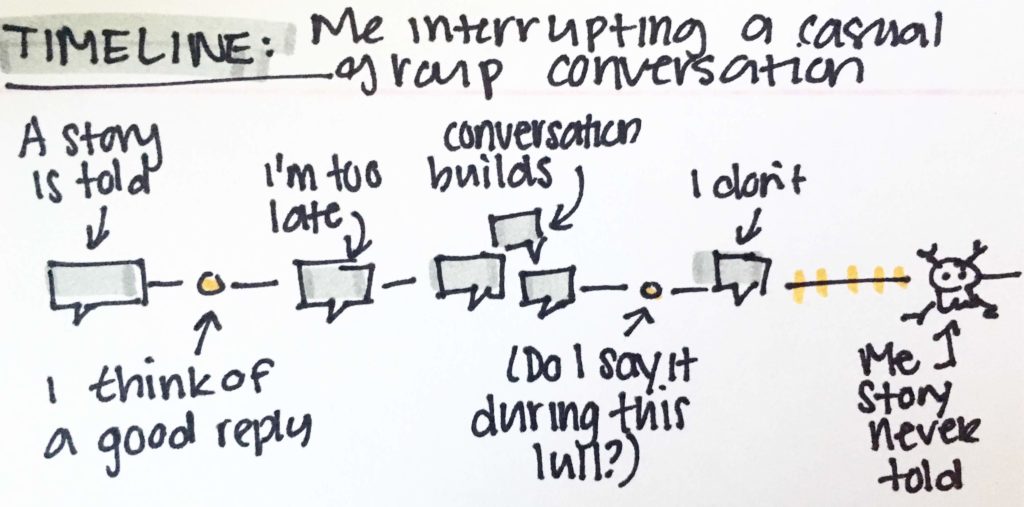

A caucus (and specifically an unmoderated caucus) is a type of meeting with no rules about who talks in what order or for how long. Instead folks jump in whenever they have something to say. The caucus probably sounds akin to some of your business meetings: most teams consider this meeting setup ‘not too formal’ and therefore lean on it in some format. […]

In caucuses you can’t [pause to consider what to say] because of the unwritten caucus rule:

The first person to utter something gets the floor.

That delightfully informal dynamic turns out to be not so delightful.

To wit: if you have something you want to say, you have to stop listening to the person currently speaking and instead focus on when they’re gonna pause or finish so you can leap into that nanosecond of silence and be the first to utter something.

I wanted to punch through my computer in agreement.

I remember sometime last year going through a women’s leadership workshop and mentioning how I thought I was getting better at being more aggressive and speaking up during meetings. The facilitator (bless her) followed up to say that I shouldn’t have to change who I am to be a good leader. That I shouldn’t feel like I have to be a more extroverted to be a good leader or even a good co-worker. I liked this idea, but it was hard for me to see how to do that. If I didn’t get my voice in the 25-minute-meeting-that-I-am-always-time-conscious-is-ending-soon-so-I’ll-hold-my-comment-even-though-we-always-go-over-time-with-someone’s-“one-quick’-thing,” then I am nonexistent and someone else would just make the decision.

Remote meetings are hard because they exacerbate our already bad meetings and cause everyone to feel it. Most importantly, the alpha meeting folks like leaders actually have to wait their turn and that means (for them) remote meeting suck and there should be no remote workers. (just kidding, you should read her followup articles on ways to improve (remote) meetings and research on successful companies).

I should still be better at sticking to my guns and feeling comfortable pausing but bringing up an issue later, but that’s a separate issue. Meetings do suck, but they could be better.

This meetings thing made me think about the importance of testing with “stress cases.” In technology, stress cases or so-called edge cases are less likely scenarios that the system hasn’t been built to handle (or can handle well). This is something I feel strongly about as a way just to make the whole product experience improve (listen to this fun podcast on the curb-cut effect).

Example you might have encountered: You have a long name name that doesn’t fit in the form you’re required to fill out.

Someone somewhere had to make the decision “a name wouldn’t be more than 10 characters, let’s just cut it off there.”

What I think nice is about the industry I’m working in now is the requirement to cover all the stress cases. We need to meet people where ever they are and make sure they have access to the service, whether than means using plain language, making sure our site is accessible, or using the technology that is the most widely available. I think folks can be enticed by the lure of innovation as using the newest technology, but it’s just as valuable for a problem to be solved by innovating on ‘how to bring it to more people using existing channels.’ I don’t mind hard problems that are unattractive. I’m a hard problem that’s unattractive.

That all brings me back to — people are complicated and can’t be reduced to good or bad and the harder you try, the more frustrated you’ll be. You can really only do you best and keep trying to learn, grow, and help others do so too, if you can. I wouldn’t want to stay the person I was even back in college and I’m glad I haven’t. Thanks, humanities education.

* He is me. When my friends say they don’t like his style of story-telling their definitely just saying they don’t like me. Carissa.